Long ago, in 1985, personal computers came in two general categories: the friendly, childish game machine used for fun (exemplified by Atari and Commodore products); and the boring, beige adult box used for business (exemplified by products from IBM). The game machines became fascinating technical and artistic platforms that were of limited real-world utility. The IBM products were all utility, with little emphasis on aesthetics and no emphasis on fun. Into this bifurcated computing environment came the Commodore Amiga 1000. This personal computer featured a palette of 4096 colors, unprecedented animation capabilities, four-channel stereo sound, the capacity to run multiple application simultaneously, a graphical user interface, and powerful processing potential. It was the world’s first true multimedia personal computer.

The Amiga’s capacity to store and display color photographs, manipulate video (giving amateurs access to professional tools), and use recordings of real-world sound were the seeds of the digital media future: digital cameras, Photoshop, MP3 players, and even YouTube, Flickr, and the blogosphere. I examine different facets of the platform — from Deluxe Paint to AmigaOS to Cinemaware — in each chapter, creating a portrait of the platform and the communities of practice that surrounded it. Of course, the Amiga was not perfect: the DOS component of the operating system was clunky and ill-matched, for example, and crashes often accompanied multitasking attempts. And Commodore went bankrupt in 1994. But for a few years, the Amiga’s technical qualities were harnessed by engineers, programmers, artists, and others to push back boundaries and transform the culture of computing.

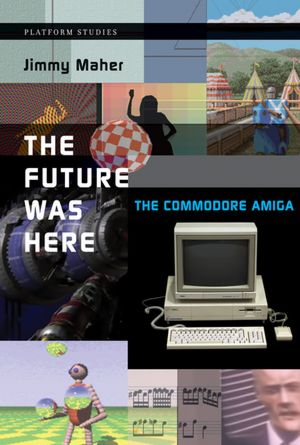

The materials on this web site are meant to accompany and enhance the material found in the Platform Studies volume about the Amiga, The Future Was Here, written by myself, Jimmy Maher, and published in 2012 by the MIT Press. It can be purchased from the MIT Press’s online store, from Amazon, from Barnes and Noble, or from brick-and-mortar booksellers worldwide. Readers of the book may also be interested in my personal blog, The Digital Antiquarian.